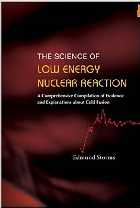

Pages: 340

Publisher: World Scientific Publishing Company

Year: 2007

ISBN: 9812706208

ISBN: 978-9812706201

March 23, 1989 can now be acknowledged as a major event in the long history of scientific discovery, on par with the discovery of fission, which gave us the atomic bomb and electrical power from nuclear reactors. On this date, Profs. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons announced to the world a new nuclear process they claimed was a method to fuse two deuterons together. For many reasons, their work has been rejected and used as an example of bad science. Only now about 17 years later and after a lot of hard work by hundreds of open-minded scientists can the importance of the discovery be fully understood and appreciated. It is the challenge of this book to assemble the evidence provided by numerous studies done at laboratories located all over the world and show that a new and important discovery was actually made, in opposition to what many people presently believe.

Who are these men who were threatened and mocked after making such an historical discovery? Very few people knew Stan Pons as the chairman of the Chemistry Department at the University of Utah. However, many people in science recognized Martin Fleischman?s name and reputation. He is a major contributor to and teacher in the field known as electrochemistry. Born in Czechoslovakia and narrowly escaping the Nazi plague, he settled in England where since 1967 he taught at the University Southampton until he retired. He was awarded just about every honor England has to offer a scientist. Hearing his name, many people trained in chemistry took notice, at least at first. However, as frequently happens when important discoveries are made, a vocal group of influential people rejected the new idea he and Pons put forth. Fortunately, a few stubborn people continued to work in obscurity and have now proven the claims of Fleischmann and Pons to be real. In so doing, they risked their reputation and, in a few cases, their livelihood. Even Pons had to emigrate to France to avoid the harsh treatment provided by his own country.

This book is mainly about the science of what was discovered and my personal experience. The general history of how events unfolded read elsewhere. In addition, several other goals have been attempted. Many people have contacted me wanting to learn about the subject and how they might see the cold fusion effect for themselves. Hopefully, this book can answer their many questions and show them where to look for more information. My second goal is to summarize what has been done in the many laboratories throughout the world. Such a summary is necessary because many observations are not accessible in easily searched journals and conventional databases. Instead, much work is only described in obscure conference proceedings. How these proceedings might be obtained is explained in Appendix D. My third goal is to describe what took place at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), where I worked when the announcement was made by Fleischmann and Pons. Everyone who was involved in trying to replicate the claims at LANL remembers the intellectual excitement at the Laboratory as being in the highest tradition of science. Such unique events are worth remembering and sharing as rare examples of what can occasionally happen.

Finally, I hope when the considerable collection of observations are viewed in their totality, rational evaluation will replace blind skepticism and unfounded ignorance. My opinions need not be accepted for what has been observed because more than 1060 publications have been cited in which the primary information can be found. Indeed, only by viewing a wide assortment of observations can an understanding be achieved. This situation is rather like trying to visualize a complex jigsaw puzzle that makes sense only after a large number of pieces have been assembled. In this case, some of the pieces are so strange it is hard to believe they belong to the same puzzle and many critical pieces are still missing. As a result, little agreement can be found among scientists about what the puzzle actually looks like.

In other words, unlike many scientific fields these days, this one is driven by observation rather than by theory. No theory explains all of what is known to be true, even though many explanations have been proposed?some plausible and some not. At this stage, theories are expected to be incomplete and very limited in their application, rather like the maps provided by early explorers or like biology before genes were understood. To make matters worse, many times people are not clear on which part of their theory is based on accepted knowledge and which part is based on imagination?again very much like early maps. Nevertheless, it is important to realize that acceptance of data is not dependent on an explanation being provided, any more than a river can be ignored just because it is not on the map. Data stands on its accuracy, consistency, and eventually on universal experience. Therefore, my main effort will be to show what is known and separate this clearly from what is not known without trying to fill the gap with imagination. This is treasure hunt using clues to shrink the large area of ignorance to a smaller area where we can start digging. As we dig, small nuggets of understanding will emerge, which should be carefully examined and hopefully accepted. At the very least, the sincere and competent efforts made by many people to understand this intriguing and sometimes frustrating phenomenon can be more fully appreciated.

After reading all that has been published about the subject and enjoying many successful replications, I?m absolutely certain the basic claims are correct and are caused by a previously unobserved nuclear mechanism operating in complex solid structures. Consequently, this book is not an unbiased description of the controversy. This is not to say that all studies are correct. In fact, many studies contain significant errors and a few are completely wrong. Nevertheless, enough good work has been published to clearly show the reality of the phenomenon. My task is to make this reality easy to understand. Summarizing only the main conclusions reduces the temptation to speculate and mathematical justifications are completely avoided.

I would like to apologize to those who consider themselves ?skeptics,? which is an honorable title I sometimes assume for myself. In the future, perhaps by the time you read this book, cold fusion will be an accepted phenomenon and the idea of someone doubting its reality will be as improbable as someone doubting the Earth goes around the Sun. My harping on the reality of cold fusion will look silly and unnecessary. Unfortunately, at the present time, many people still think the idea is nonsense and approach the subject the way the Church approached Heliocentric astronomy 500 years ago. I hope this book will be accepted as a better telescope. If all of this considerable body of work is dismissed as error, what does this say about the competence of modern science? Is it rational to believe that many modern tools only give the wrong answer when they are applied to cold fusion?

While at LANL, as described in Chapter 2, I had a unique view of how events unfolded, at least within LANL. During this time, I investigated the science of cold fusion and, after ?retiring? in 1991 and leaving LANL for good in 1993, the work continued in my own laboratory. This experience taught me to accept the reality of these ?impossible? claims. Chapter 3 summarizes these lessons. Evidence provided by everyone else is discussed in later chapters, where a huge collection of experience is evaluated and put into perspective. Even people working in the field are not fully aware of what has been discovered. As the reader will soon learn, the novel effects occur only in unique and very small locations. These locations are discussed in Chapter 5. Methods used to initiate the anomalous effects are described in Chapter 6 and detection of the resulting behavior is discussed in Chapter 7. Development of a proper theory has been one of the great challenges of the field. Consequently, some explanations are offered and evaluated in Chapter 8. As will become clear, cold fusion is not cold, expect in comparison to hot fusion, and it is not normal fusion. Explanations, rather than being a part of high-energy physics, involve solid-state physics and chemistry. Consequently, the observations need to be viewed through a different lens than is applied to hot fiusion. Finally, Chapter 9 tries to show what all this information means and what should be done next. The implications of this discovery are so profound that people need to accept its reality and be prepared to enjoy the consequences of its eventual application. The only uncertainties remaining are which country will first gain the benefits and how soon.

As for my background, I came to the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Los Alamos, New Mexico, first in 1956 and again in 1957 as a summer student and returned as a staff member in 1958 after getting a Ph.D. in radiochemistry from Washington University, St. Louis. Prof. Joseph Kennedy, my research professor, had been the director of the Chemical and Metallurgical Division at the secret laboratory in Los Alamos during the war and co-discovered plutonium. Thanks to his encouragement, I joined a steady stream of graduates from the University he was recruiting for the new Laboratory. This was a time when the Laboratory was changing from the primitive conditions existing during the war to what was to become a major national laboratory located in a place of unusual beauty. It was an ideal place to do creative work because competent people who knew science and scientists administered the laboratory at that time. I was hired to study the thermodynamic and phase relationship properties of very high melting point materials1 used in reactors designed to provide power or propulsion in space, a useful and exciting subject even though the intended machines were never built. Nevertheless, the work was productive and satisfying, resulting in more than 100 publications, a book2, and teaching sabbaticals at several universities including the University of Vienna, Austria. I did not need another project and I was content to believe the theories everyone else accepts in nuclear physics. Besides, Carol, my wife, could have done without the scientific mistress cold fusion later became. To some extent, this book describes a personal awakening to the realization that what is taught and thought to be true in nuclear physics is only partly correct. A totally unexplored environment in which nuclear interaction can take place apparently exists within solid materials.